- Преподавателю

- Иностранные языки

- Материалы к урокам, посвященным творчеству Б. Шоу с заданием

Материалы к урокам, посвященным творчеству Б. Шоу с заданием

| Раздел | Иностранные языки |

| Класс | - |

| Тип | Конспекты |

| Автор | Левкович Е.А. |

| Дата | 01.12.2015 |

| Формат | docx |

| Изображения | Есть |

LESSONS 1-2

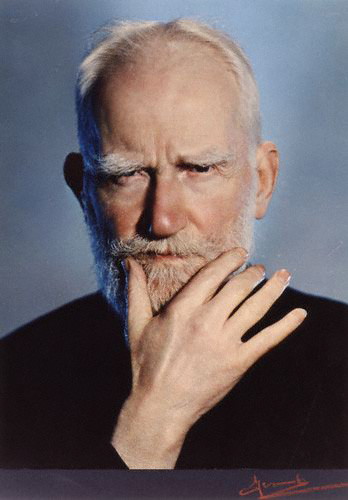

BERNARD SHAW (1856-1950)

There was a time when the English theatre stood very high. The English people still like to call their country "the land of Shakespeare," but this is a glory of the past. In later ages the English theatre, never reached the height it had known in Shakespeare's time. In the XIX century the English theatre was very poor.

The reasons for the poverty of the English theatre and drama lay, firstly, in the fact, that at that time the theatre in England had become a purely commercial enterprise. The chief aim of the managers was to squeeze money out of the theatre. They tried to please the public - mostly rich people who could pay well to be amused - and avoided all political subjects.

To create a new theatre and a drama of social significance became the aim of Bernard Shaw and of a few other writers, theatrical managers and actors of his time. The attempt was very nearly hopeless under the existing conditions. In fact, the English theatre is still in the present day one of the poorest in the world. Nevertheless the attempt had some important results. First of all it brought onto the English stage plays by the best masters of the drama, the Russian realistic drama of Chekhov and Tolstoy, mid a little later the plays of Gorki. Next it brought into life 1 Bernard Shaw's own dramatic talent. .His first play "Widowers' Houses"2 (see the extract below) was performed in 1892. Both (he bourgeois public and the critics immediately attacked Bernard Shaw, calling him cynical, pessimistic and immoral.

This first play was followed by many other comedies:"!,Mrs. Warren's Profession," 3 "The Man of Destiny,"4 "Candida,"5 "Man and Superman,"6 etc.

Shaw's way of writing is very peculiar: he says true things in such a way that at first one is not sure whether he is joking or serious. Sometimes Shaw even makes a sort of game out of his jokes and witty words. In these cases the jokes are often funny; but they have no purpose or depth in them. On the other hand, though Bernard Shaw read Marx in his youth, he never mastered his teaching and, limited by his bourgeois outlook, never really understood the Marxist point of view. So having but a very imperfect idea of the future development of society, Shaw was sometimes inclined to build very complicated and dim theories of his own. Unable to find his way out of them, he would then lose something of his acute hold on reality7 and his sharp criticism of it. This meant that at such times his work became less realistic, less lively and hopeful of the future8 and his views more coldly sceptical. In his old age Bernard Shaw visited the Soviet Union. When he came back to England he spoke of the USSR as of a country in which lie all the hopes of humanity, for it shows man his way into the future.

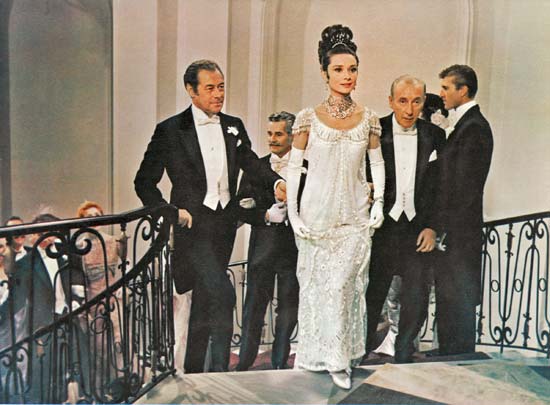

His best plays, such as "Widowers' Houses," "Pygmalion," 9 and a few others are continually staged and enjoyed by the Soviet public for their fun, their wit and their exposure of capitalist reality

TASKS to the LESSONS 1-2

Task 1. Read and translate the text.

Task 2. Pick out new words in your vocabulary.

Task 3. Compose 5 sentences with as many new words as possible.

Task 4. Make a summary of the author's life in chronological order.

LESSONS 3-4

PYGMALION: A ROMANCE IN FIVE ACTS

by George Bernard Shaw

PREFACE TO PYGMALION - A PROFESSOR OF PHONETICS

AS WILL BE SEEN later on, Pygmalion needs, not a preface, but a sequel, which I have supplied in its due place. The English have no respect for their language, and will not teach their children to speak it. They cannot spell it so abominably that no man can teach himself what it sounds like. It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him. German and Spanish are accessible to foreigners: English is not accessible even to Englishmen. The reformer England needs today is an energetic phonetic enthusiast: that is why I have made such a one the hero of a popular play. They have been heroes of that kind crying in the wilderness for many years past. When I became interested in the subject towards the end of the eighteen-seventies, the illustrious Alexander Melville Bell, the inventor of Visible Speech, had emigrated to Canada, where his son invented the telephone; but Alexander J. Ellis was still a London patriarch, with an impressive head always covered by a velvet skull cap, for which he would apologize to public meetings in a very courtly manner. He and Tito Pagliardini, another phonetic veteran, were men whom it was impossible to dislike. Henry Sweet, then a young man, lacked their sweetness of character: he was about as conciliatory to conventional mortals as Ibsen or Samuel Butler. His great ability as a phonetician (he was, I think, the best of them all at his job) would have entitled him to high official recognition, and perhaps enabled him to popularize his subject, but for his Satanic contempt for all academic dignitaries and persons in general who thought more of Greek than of phonetics.

Once, in the days when the Imperial Institute rose in South Kensington, and Joseph Chamberlain was booming the Empire, I induced the editor of a leading monthly review to commission an article from Sweet on the imperial importance of his subject. When it arrived, it contained nothing but a savagely derisive attack on a professor of language and literature whose chair Sweet regarded as proper to a phonetic expert only. The article, being libellous, had to be returned as impossible; and I had to renounce my dream of dragging its author into the limelight. When I met him afterwards, for the first time for many years, I found to my astonishment that he, who had been a quite tolerably resentable young man, had actually managed by sheer scorn to alter his personal appearance until he had become a sort of walking repudiation of Oxford and all its traditions. It must have been largely in his own despite that he was squeezed into something called a Readership of phonetics there. The future of phonetics rests probably with his pupils, who all swore by him; but nothing could bring the man himself into any sort of compliance with the university to which he nevertheless clung by divine right in an intensely Oxonian way. I daresay his papers, if he has left any, include some satires that may be published without too destructive results fifty years hence. He was, I believe, not in the least an illnatured man: very much the opposite, I should say; but he would not suffer fools gladly.

Those who knew him will recognize in my third act the allusion to the patent shorthand in which he used to write postcards, and which may be acquired from a four and sixpenny manual published by the Clarendon Press. The postcards which Mrs Higgins describes are such as I have received from Sweet. I would decipher a sound which a cockney would represent by zerr, * and a Frenchman by seu, and then write demanding with some heat what on earth it meant. Sweet, with boundless contempt for my stupidity, would reply that it not only meant but obviously was the word Result, as no other word containing that sound, and capable of making sense with the context, existed in any language spoken on earth. That less expert mortals should require fuller indications was beyond Sweet's patience. Therefore, though the whole point of his Current Shorthand is that it can express every sound in the language perfectly, vowels as well as consonants, and that your hand has to make no stroke except the easy and current ones with which you write m, n, and u, l, p, and q, scribbling them at whatever angle comes easiest to you, his unfortunate determination to make this remarkable and quite legible script serve also as a shorthand reduced it in his own practice to the most inscrutable of cryptograms. His true objective was the provision of a full, accurate, legible script for our noble but ill-dressed language; but he was led past that by his contempt for the popular Pitman system of shorthand, which he called the Pitfall system. The triumph of Pitman was a triumph of business organization: there was a weekly paper to persuade you to learn Pitman: there were cheap textbooks and exercise books and transcripts of speeches for you to copy, and schools where experienced teachers coached you up to the necessary proficiency. Sweet could not organize his market in that fashion. He might as well have been the Sybil who tore up the leaves of prophecy that nobody would attend to. The four and sixpenny manual, mostly in his lithographed handwriting, that was never vulgarly advertized,may perhaps someday be taken up by a syndicate and pushed upon the public as the Times pushed the Encyclopaedia Britannica; but until then it will certainly not prevail against Pitman. I have bought three copies of it during my lifetime; and I am informed by the publishers that its cloistered existence is still a steady and healthy one. I actually learned the system two several times; and yet the shorthand in which I am writing these lines is Pitman's. And the reason is, that my secretary cannot transcribe Sweet, having been perforce taught in the schools of Pitman. Therefore Sweet railed at Pitman as vainly as Their sites railed at Ajax: his raillery, however it may have eased his soul, gave no popular vogue to Current Shorthand.

Pygmalion Higgins is not a portrait of Sweet, to whom the adventure of Eliza Doolittle would have been impossible; still, as will be seen, there are touches of Sweet in the play. With Higgins's physique and temperament Sweet might have set the Thames on fire. As it was, he impressed himself professionally on Europe to an extent that made his comparative personal obscurity, and the failure of Oxford to do justice to his eminence, a puzzle to foreign specialists in his subject. I do not blame Oxford, because I think Oxford is quite right in demanding a certain social amenity from its nurslings (heaven knows it is not exorbitant in its requirements!); or although I well know how hard it is for a man of genius with a seriously underrated subject to maintain serene and kindly relations with the men who underrate it, and who keep all the best places for less important subjects which they profess without originality and sometimes without much capacity for them, still, if he overwhelms them with wrath and disdain, he cannot expect them to heap honors on him. Of the later generations of phoneticians I know little. Among them towers the Poet Laureate, to whom perhaps Higgins may owe his Miltonic sympathies, though here again I must disclaim all portraiture. But if the play makes the public aware that there are such people as phoneticians, and that they are among the most important people in England at present, it will serve its turn.

I wish to boast that Pygmalion has been an extremely successful play all over Europe and North America as well as at home. It is so intensely and deliberately didactic, and its subject is esteemed so dry, that I delight in throwing it at the heads of the wiseacres who repeat the parrot cry that art should never be didactic. It goes to prove my contention that great art can never be anything else.

Finally, and for the encouragement of people troubled with accents that cut them off from all high employment, I may add that the change wrought by Professor Higgins in the flower girl is neither impossible nor uncommon. The modern concierge's daughter who fulfils her ambition by playing the Queen of Spain in Ruy Blus at the Theatre Francais is only one of many thousands of men and women who have sloughed off their native dialects and acquired a new tongue. But the thing has to be done scientifically, or the last state of the aspirant may be worse than the first. An honest and natural slum dialect is more tolerable than the attempt of a phonetically untaught persons to imitate the vulgar dialect of the golf club; and I am sorry to say that in spite of the efforts of our Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, there is still too much sham golfing English on our stage, and too little of the noble English of Forbes Robertson.

TASKS to the LESSONS 3-4

Task 1. Read and translate the text.

Task 2. Pick out new words in your vocabulary.

Task 3. Summarize the text in five sentences.

LESSONS 5-6

ACT FOUR

HIGGINS. I presume you don't pretend that I have treated you badly?

LIZA. No.

HIGGINS. I am glad to hear it. (He moderates his tone). Perhaps you're tired after the strain of the day. Will you have a glass of champagne? (He moves towards the door).

LIZA. No. (Recollecting her manners) Thank you.

HIGGINS (good-humored again) This has been coming on you for some days. I suppose it was natural for you to be anxious about the garden party. But thats all over now. (He pats her kindly on the shoulder. She writhes). There's nothing more to worry about.

LIZA. No. Nothing more for you to worry about. (She suddenly rises and gets away from him by going to the piano bench, where she sits and hides her face). Oh God! I wish I was dead.

HIGGINS (staring after her in sincere surprise) Why? In Heaven's name, why? (Reasonably, going to her) Listen to me, Eliza. All this irritation is purely subjective.

LIZA. I don't understand. I'm too ignorant.

HIGGINS. It's only imagination. Low spirits and nothing else. Nobody's hurting you. Nothing's wrong. You go to bed like a good girl and sleep it off. Have a little cry and say your prayers: that will make you comfortable.

LIZA. I heard your prayers. "Thank God it's all over!"

HIGGINS (impatiently) Well, don't you thank God it's all over? Now you are free and can do what you like.

LIZA (pulling herself together in desperation) What am I fit for? What have you left me fit for? Where am I to go? What am I to do? What's to become of me?

HIGGINS (enlightened, but not at all impressed) Oh that's what's worrying you, is it? (He thrusts his hands into his pockets, and walks about in his usual manner, rattling the contents of his pockets, as if condescending to a trivial subject out of pure kindness). I shouldn't bother about it if I were you. I should imagine you won't have much difficulty in settling yourself somewhere or other, though I hadn't quite realized that you were going away. (She looks quickly at him: he does not look at her, but examines the dessert stand on the piano and decides that he will eat an apple). You might marry, you know. (He bites a large piece out of the apple and munches it noisily). You see, Eliza, all men are not confirmed old bachelors like me and the Colonel. Most men are the marrying sort (poor devils!); and you're not bad-looking: it's quite a pleasure to look at you sometimes- not now, of course, because you're crying and looking as ugly as the very devil; but when you're all right and quite yourself, you're what I should call attractive. That is, to the people in the marrying line, you understand. You go to bed and have a good nice rest; and then get up and look at yourself in the glass; and you won't feel so cheap. Eliza again looks at him, speechless, and does not stir. The look is quite lost on him: he eats his apple with a dreamy expression of happiness, as it is quite a good one.

HIGGINS (a genial afterthought occurring to him) I daresay my mother could find some chap or other who would do very well.

LIZA. We were above that at the corner of Tottenham Court Road.

HIGGINS (waking up) What do you mean?

LIZA. I sold flowers. I didn't sell myself. Now you've made a lady of me I'm not fit to sell anything else. I wish you'd left me where you found me.

HIGGINS (slinging the core of the apple decisively into the grate) Tosh, Eliza. Don't you insult human relations by dragging all this cant about buying and selling into it. You needn't marry the fellow if you don't like him

LIZA. What else am I to do?

HIGGINS. Oh, lots of things. What about your old idea of a florist's shop? Pickering could set you up in one: he has lots of money. (Chuckling) He'll have to pay for all those togs you have been wearing today; and that, with the hire of the jeweler, will make a big hole in two hundred pounds. Why, six months ago you would have thought it the millennium to have a flower shop of your own. Come! You'll be all right. I must clear off to bed: I'm devilish sleepy. By the way, I came down for something: I forget what it was.

LIZA. Your slippers.

HIGGINS. Oh yes, of course. You shied them at me. (He picks them up, and is going out when she rises and speaks to him).

LIZA. Before you go, sir-

HIGGINS (dropping the slippers in his surprise at her calling him Sir)Eh? LIZA. Do my clothes belong to me or to Colonel Pickering?

HIGGINS (coming back into the room as if her question were the very climax of unreason) What the devil use would they be to Pickering?

LIZA. He might want them for the next girl you pick up to experiment on. HIGGINS (shocked and hurt) Is that the way you feel towards us?

LIZA. I don't want to hear anything more about that. All I want to know is whether anything belongs to me. My own clothes were burnt.

HIGGINS. But what does it matter? Why need you start bothering about that in the middle of the night?

LIZA. I want to know what I may take away with me. I don't want to be accused of stealing. HIGGINS (now deeply wounded) Stealing! You shouldnt have said that,

Eliza. That shows a want of feeling.

LIZA. I'm sorry. I'm only a common ignorant girl; and in my station I have to be careful. There can't be any feelings between the like of you and the like of me. Please will you tell me what belongs to me and what doesnt?

HIGGINS (very sulky) You may take the whole damned houseful if you like. Except the jewels. They're hired. Will that satisfy you?

(He turns on his heel and is about to go in extreme dudgeon).

LIZA (drinking in his emotion like nectar, and nagging him to provoke a further supply) Stop, please. (She takes off her jewels). Will you take these to your room and keep them safe? I dont want to run the risk of their being missing.

HIGGINS (furious) Hand them over. (She puts them into his hands). If these belonged to me instead of to the jeweller, I'd ram them down your ungrateful throat. (He perfunctorily thrusts them into his pockets, unconsciously decorating himself with the protruding ends of the chains).

LIZA (taking a ring off) This ring isn't the jeweller's: it's the one you bought me in Brighton. I dont want it now. (Higgins dashes the ring violently into the fireplace, and turns on her so threateningly that she crouches over the piano with her hands over her face, and exclaims) Don't you hit me.

HIGGINS. Hit you! You infamous creature, how dare you accuse me of such a thing? It is you who have hit me. You have wounded me to the heart.

LIZA (thrilling with hidden joy) I'm glad. Ive got a little of my own back, anyhow.

HIGGINS (with dignity, in his finest professional style) You have caused me to lose my temper: a thing that has hardly ever happened to me before. I prefer to say nothing more to-night. I am going to bed.

LIZA (pertly) You'd better leave a note for Mrs Pearce about the coffee; for she won't be told by me.

HIGGINS (formally) Damn Mrs Pearce; and damn the coffee; and damn you; and damn my own folly in having lavished my hard-earned knowledge and the treasure of my regard and intimacy on a heartless guttersnipe. (He goes out with impressive decorum, and spoils it by slamming the door savagely).

Eliza smiles for the first time; expresses her feelings by a wild pantomine in which an imitation of Higgins's exit is confused with her own triumph; and finally goes down on her knees on the hearthrug to look for the ring.

TASKS to the LESSONS 5-6

Task 1. Read and translate the text.

Task 2. Pick out new words in your vocabulary.

Task 3. Describe the characters of this story.

LESSONS 7-8

ACT FIVE

Eliza enters, sunny, self-possessed, and giving a staggeringly convincing exhibition of ease of manner. She carries a little work-basket, and is very much at home. Pickering is too much taken aback to rise.

LIZA. How do you do, Professor Higgins? Are you quite well?

HIGGINS (choking) Am I- (He can say no more).

LIZA. But of course you are: you are never ill. So glad to see you again, Colonel Pickering. (He rises hastily; and they shake hands). Quite chilly this morning, isnt it? (She sits down on his left. He sits beside her).

HIGGINS. Dont you dare try this game on me. I taught it to you; and it doesnt take me in. Get up and come home; and don't be a fool.

Eliza takes a piece of needlework from her basket, and begins to stitch at it, without taking the least notice of this outburst.

MRS HIGGINS. Very nicely put, indeed, Henry. No woman could resist such an invitation.

HIGGINS. You let her alone, mother. Let her speak for herself. You will jolly soon see whether she has an idea that I haven't put into her head or a word that I haven't put into her mouth. I tell you I have created this thing out of the squashed cabbage leaves of Covent Garden; and now she pretends to play the fine lady with me.

MRS HIGGINS (placidly) Yes, dear; but you'll sit down, won't you?

Higgins sits down again, savagely.

LIZA (to Pickering, taking no apparent notice of Higgins, and working away deftly) Will you drop me altogether now that the experiment is over, Colonel Pickering?

PICKERING. Oh don't. You mustnt think of it as an experiment. It shocks me, somehow.

LIZA. Oh, I'm only a squashed cabbage leaf-

PICKERING (impulsively) No.

LIZA (continuing quietly)- but I owe so much to you that I should be very unhappy if you forgot me.

PICKERING. It's very kind of you to say so, Miss Doolittle.

LIZA. It's not because you paid for my dresses. I know you are generous to everybody with money. But it was from you that I learnt really nice manners; and that is what makes one a lady, isn't it? You see it was so very difficult for me with the example of Professor Higgins always before me. I was brought up to be just like him, unable to control myself, and using bad language on the slightest provocation. And I should never have known that ladies and gentlemen didn't behave like that if you hadn't been there.

HIGGINS. Well!!

PICKERING. Oh, that's only his way, you know. He doesn't mean it.

LIZA. Oh, I didn't mean it either, when I was a flower girl. It was only my way. But you see I did it; and that's what makes the difference after all.

PICKERING. No doubt. Still, he taught you to speak; and I couldn't have done that, you know.

LIZA (trivially) Of course: that is his profession.

HIGGINS. Damnation!

LIZA (continuing) It was just like learning to dance in the fashionable way: there was nothing more than that in it. But do you know what began my real education?

PICKERING. What?

LIZA (stopping her work for a moment) Your calling me Miss Doolittle that day when I first came to Wimpole Street. That was the beginning of self-respect for me. (She resumes her stitching). And there were a hundred little things you never noticed, because they came naturally to you. Things about standing up and taking off your hat and opening doors-

PICKERING. Oh, that was nothing.

LIZA. Yes: things that shewed you thought and felt about me as if I were something better than a scullery-maid; though of course I know you would have been just the same to a scullery-maid if she had been let into the drawing room. You never took off your boots in the dining room when I was there.

PICKERING. You mustn't mind that. Higgins takes off his boots all over the place.

LIZA. I know. I am not blaming him. It is his way, isn't it? But it made such a difference to me that you didn't do it. You see, really and truly, apart from the things anyone can pick up (the dressing and the proper way of speaking, and so on), the difference between a lady and a flower girl is not how she behaves, but how she's treated. I shall always be a flower girl to Professor Higgins, because he always treats me as a flower girl, and always will; but I know I can be a lady to you, because you always treat me as a lady, and always will.

MRS HIGGINS. Please dont grind your teeth, Henry.

PICKERING. Well, this is really very nice of you, Miss Doolittle.

LIZA. I should like you to call me Eliza, now, if you would.

PICKERING. Thank you. Eliza, of course.

LIZA. And I should like Professor Higgins to call me Miss Doolittle.

HIGGINS. I'll see you damned first.

MRS HIGGINS. Henry! Henry!

PICKERING (laughing) Why dont you slang back at him? Dont stand it. It would do him a lot of good.

LIZA. I cant. I could have done it once; but now I cant go back to it. Last night, when I was wandering about, a girl spoke to me; and I tried to get back into the old way with her; but it was no use. You told me, you know, that when a child is brought to a foreign country, it picks up the language in a few weeks, and forgets its own. Well, I am a child in your country. I have forgotten my own language, and can speak nothing but yours. Thats the real break-off with the corner of Tottenham Court Road. Leaving Wimpole Street finishes it.

PICKERING (much alarmed) Oh! but youre coming back to Wimpole Street, arnt you? Youll forgive Higgins?

HIGGINS (rising) Forgive! Will she, by George! Let her go. Let her find out how she can get on without us. She will relapse into the gutter in three weeks without me at her elbow.

TASKS to the LESSONS 7-8

Task 1. Read and translate the text.

Task 2. Pick out new words in your vocabulary.

Task 3. What is the main idea of the extract?

Task 4. Give pluses and minuses of the extract.

Task 5. Make the literary analysis of the text according to the plan or the presentation using Microsoft Power Point Presentation or Movie Maker.